The New York Times

Unseen Army Keeps the Show Going On

by MARK BLANKENSHIP on August 3, 2008

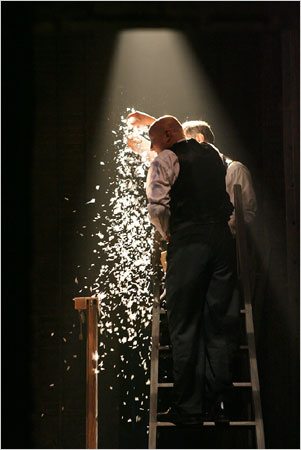

WITH only four actors playing over 20 roles, “Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps” is madcap onstage. But life in the wings is just as manic.

For 90 minutes crew members snake past one another with ladders, smoke machines and life-size dummies, all without making a sound. But most patrons don’t even know these backstage artists exist.

It’s the same with any production: after opening night, directors and designers usually move to their next projects, while a small army stays behind to safeguard their artistic vision. Take Nevin Hedley, who has been the production stage manager of “The 39 Steps,” a spoof of Hitchcock’s 1935 thriller, since its pre-Broadway run at the Huntington Theater in Boston last fall. (It is currently playing at the Cort.) During performances he sits behind a bank of flickering monitors that let him see the stage, and as he follows along in his script, he delivers cues via headset to crew members throughout the theater.

But he’s not sitting idle, occasionally telling the light board operator to prepare for a blackout. “The 39 Steps” is bursting with cues — there are 190 sound cues alone, a high tally for a play — so Mr. Hedley must remain alert.

Credit Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

“Unlike a lot of shows, sections of this move so fast that you can’t think,” he said. “If you stop to wonder what’s next, the moment is gone.”

Mr. Hedley said there is artistic satisfaction in his high-pressure work. “You’re sort of like what a conductor is to an orchestra,” he said. “Every light, every sound: it all happens when the person calling the show says, ‘Go.’ You can finesse the elements under your control to seem like a seamless part of the production.”

Like many stage managers Mr. Hedley also serves as a proxy director, giving notes to actors and overseeing rehearsals with understudies and replacement performers.

Similarly, costume designers rely on wardrobe supervisors and design associates to sustain their work.

That’s an especially tall order for “Wicked.” The costume designer, Susan Hilferty, created individualized looks for almost every character, even in the ensemble, and each new cast member gets a fresh, handmade set of clothes.

Ms. Hilferty checks in on the New York production, but she also counts on the wardrobe supervisor, Alyce Gilbert, a stalwart whose credits include the original productions of “A Chorus Line” and “Dreamgirls.”

Ms. Gilbert arrives at the George Gershwin Theater hours before the start of each performance, checking costumes for wear and consulting with a team of wardrobe employees. She also makes frequent trips to the Manhattan shops that build the “Wicked” costumes. Keeping an eye on practical concerns, she makes sure each custom-made piece will function correctly onstage. (Ms. Hilferty’s design associate monitors aesthetic choices like fabric selection.)

Ms. Gilbert is also primed for emergencies. For instance if the actress playing Elphaba realizes she is not up to the vocal demands of her role that day, then she is replaced in midperformance. That’s when Ms. Gilbert marshals a team to get the new Elphaba dressed, while make-up artists paint her green. All this happens in a tiny curtained area just offstage, often only minutes before Elphaba’s next song.

“I’m rushing about saying, ‘Move this, carry this,’ ” Ms. Gilbert said. “It’s a small circus.”

Similarly, when one of the puppets in “The Lion King” breaks during a performance, there is no time for delicate engineering. Instead one of the show’s on-call puppet specialists must perform an ingenious bit of surgery.

Evan Sung for The New York Times

Recently one such specialist, Ilya Vett, was backstage when he received alarming news. “I got this message on the radio,” he said. “All they said was, ‘Pumbaa has lost his butt.’ ”

Pumbaa may be a friendly warthog, but without a backside, he’s much less appealing. Mr. Vett discovered that the puppet’s aluminum spine had snapped, leaving the actor inside dragging a lumpy mass, so he quickly rigged a replacement spine out of special tape and hardened it under a nearby lamp.

While tinkering with a broken motor in a lion’s head, Mr. Vett said the show’s puppetry constantly demands creative problem solving. “The execution and design is still so progressive that no matter how much you know, there’s always more to learn,” he said.

As the sound engineer for “Spamalot,” John Dory makes split-second choices throughout the show. From a large console in the back of the Shubert Theater, he controls the volume of every sound coming from the stage and the orchestra. He constantly adjusts microphone levels to ensure that sound effects, instruments and voices will blend as the show’s sound designers, Acme Sound Partners, originally intended.

Sitting at his console before a recent performance Mr. Dory explained that countless factors affect the quality of sound — humidity in the theater, an actor’s head cold — so he can never predict which sounds will need more or less amplification to seem natural. “You can’t come in here preoccupied with personal stuff, and you can’t let your mind wander, because it will come back and bite you big time,” he said.

Even when only one actor is onstage, Mr. Dory’s fingers work the faders on his console, sometimes adjusting them by a fraction of an inch. For the uninitiated it’s hard to notice how the sound is changing, since nothing is amiss with the performance.

And that’s the point. Like most backstage artists in the theater Mr. Dory succeeds when it seems the production is happening without his help.

“That’s how I like it,” he said. “My goal is for nobody to realize I’m back here. If they’re noticing me, they’re not involved in the show.”