Live Design

Another Part Of The Forest

by David Johnson & Ellen Lampert-Gréaux on September 1, 2002

For the new Broadway revival of Into the Woods, the creative team played it by the book—the storybook, that is. In re-imagining this Stephen Sondheim musical about what happens after happily ever after, director James Lapine (who also directed the original production) wanted the designers—Susan Hilferty (costumes), Doug Schmidt (sets), Brian MacDevitt (lights), Elaine McCarthy (projections), and Dan Moses Schreier (sound)–to look beyond the fairy tales that populate the show—Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, The Baker and His Wife, Little Red Riding Hood–to the actual act of storytelling, and ultimately to the books themselves.

“James wanted us to free our imaginations,” says Hilferty. “The only thing he brought to the table was a pop-up book, and we kept trying to figure out what it was we connected to in the book. It all came down to the memory of books–the idea of storytelling–and how it brings you back to childhood.”

One of the first things the team tried to establish in early meetings was an actual vocabulary of the fairy-tale world. “People would say, ‘Well it’s just fairy stories,’ as if there were a vocabulary for fairy stories, which there isn’t,” says Hilferty. “If you look back to your favorite illustrators, every single one of them is different. You look up Cinderella on the Internet, and there’s edition after edition. So we had to create our own vocabulary.”

Hilferty’s vocabulary would end up including moos, howls, oinks, and a variety of other barnyard sounds; she felt early on that giving a real voice to the various animals that populate the musical—the big bad wolf, the three pigs, and especially Jack’s beloved Milky-White—was the key to connecting the overlapping fairy-tale worlds. “This was a world in which I thought the animals should talk, because animals do talk in this world,” she says. “Though there are human events happening onstage, nobody’s surprised when a wolf walks onstage, and nobody’s surprised to see Milky-White. Just as in fairy stories, where you accept these things—a bear talks, a snake talks—what this world needs is to accommodate the animals.”

Perhaps the biggest accommodation—indeed one of the production’s major innovations—is the introduction of Milky-White as an animated being. Jack’s bovine friend was nothing more than a prop in the 1987 Broadway incarnation; today, she’s a living, breathing creature, played by actor Chad Kimball. But because the decision to animate Milky-White came well into the creative process, there was in turn a long evolution process in coming up with the right look and feel to the creature. Hilferty and her team—which included associate designers Devon Painter and Michael Sharpe and assistant designers Amanda Whidden and Chris Peterson—sketched innumerable variations of the animal, ranging from a girl with a cow’s body, to a cow with a girl’s face. “All the initial goals of the cow for me were to find this level of humanness and then to find the level of character,” Hilferty says. “This went on for a long time as we tried to get James to visualize by what I had sketched by what we were ultimately trying to figure out and accomplish.”

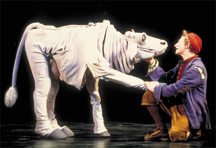

Milky-White in her final manifestation with Jack. Photo: © Joan Marcus

The final sketch was a four–legged cow that combined the idea of storytelling with the idea of movement, giving the creature something of a sad, stuffed animal quality (as in a rag doll, or Eeyore), while making it clear that an actor was playing the role.

“I broke all the rules of real cows,” Hilferty says. “It became important that the head was low because it made it sadder and sweeter. We gave a humanness to the face, and eyes that have nothing to do with a cow. I knew that this was the right idea because whenever anybody looks at the sketch they’d go, ‘Awww.’ We kept finding whenever we tried to do something different we didn’t get the same response.”

The next step was to actually make the thing, and for that Hilferty turned to fabricator Andrew Benepe. “He made the cow head and the fabrication of the cow body, but his real masterpiece is the head,” says Hilferty. Actually, the head and the neck: it is the neck that has to hold up the head. Sure, the cow’s eyes open and close, her ears flap, and she can move her mouth from side to side to mimic chewing. But the head, even though lightweight, needed to be supported. Kimball has to use crutches to create the front legs of the cow, and his head is actually over a foot away from the cow’s head. “The actor is in one place, and the head is in another, so what’s holding the head in place? And at the same time, it has to be flexible, so if you’ve got a hard spine holding it up, you’re out of luck.

“The brilliant thing Andrew did,” Hilferty continues, “was to try a coil. The coil gave support to the neck and allowed an enormous amount of flexibility. The other critical thing was that it gives some space for the actors to see. As soon as I saw it, I said, ‘Okay, we’re going to feature that. We stuffed it and wrapped it at the neck, and it immediately became not about being a cow.”

The cow’s body is deceptively simple, made up essentially of Polartec, a lightweight, fleecelike material, worn like a pair of longjohns, with a long spine connecting the tail and the neck, and a strapped-on udder. This gives Kimball the freedom of movement that Lapine and Carrafa sought in bringing Milky-White to life.

It’s telling that Milky-White elicits the same “awws” from the audience every night that Hilferty got from that final sketch of the cow. Still, doesn’t it seem odd that a costume designer gets such acclaim (Hilferty was nominated for a Tony for her work) for creating this lovable but essentially silent bovine entity? Not at all, says the designer. “The key to it is character, which is what we work with every day. That’s the difference between a costume designer and a fashion designer.”

And apparently, a set designer as well. “Doug [Schmidt] was thrilled that I was so interested in the animals,” Hilferty adds, “because it meant that he didn’t have to do them!” –David Johnson

The Forest and the Trees

“I was reluctant at first, almost hesitant,” says set designer Douglas Schmidt about designing this production of Into the Woods. “I had fond memories of the earlier Broadway version. It’s not that I didn’t want to tread the waters, but Anthony Straiges had done a great job. It was just beautiful to watch, but James Lapine was anxious to rethink the whole thing.”

Schmidt’s version was inspired by Lapine’s interest in using Victorian books as a frame for the production. “We did a lot of research into old books, looking at the typography, the binding, and the graphics, to find something that would sustain enlarging to a giant scale and not fall apart visually,” Schmidt says. After entering the world of fairy tales through a large book, three of the stories jump to life, each in its own “book” set. The “books” were built by ShowMotion in Norwalk, CT. with the intricate design detail and faux embossing by Scenic Art Studios.

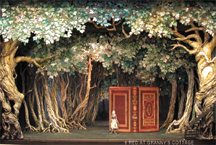

a set model by Schmidt

The books serve as houses for Cinderella, Jack (of beanstalk fame) and his mother, and the baker and his wife. One of the books revolves to create Rapunzel’s tower. There is also a finale book that the characters go back into at the end of the story. “The book metaphor worked very well and gave me permission to use the period illustrations to root our production in reality,” says Schmidt.

Schmidt created a child’s fairy-tale version of a forest, where much of the action takes place. “I looked at illustrations by English artists such as Arthur Rackham and Walter Crane,” he says. “I added a complexity to give the illustrations a magical quality. It is ominous and has a scary quality; this is important in a fairy tale.”

In Schmidt’s forest, things move around to accommodate the action. “There is a big danger you could get sick of looking at the forest, so we had to do a moveable feast,” he says. To do so, things shuffle about the stage to create the feeling that the characters have moved to another part of the forest. The trees move about on overhead tracks, with the trees and tracks also built by ShowMotion.

“Each tree has its own set of parameters of where it can move via a computer interface,” explains Schmidt. The trees reach as high as 25′ and were laser-cut out of huge sheets of aluminum, with scrolly trunks and roots based on Schmidt’s initial drawings. To add textures, fabric was dipped in a glue-based substance that was applied to the trees. “There were great globs of glue-soaked rags twisted into bark and roots. It was not an easy job,” Schmidt allows. The trees were then painted to look like the 1/2″ models and topped with leaves that have a gauzy see-through quality, allowing them to let light through.

Schmidt worked with video designer Elaine McCarthy to create projections of Cinderella’s mother and one of the giants atop Jack’s beanstalk. “We wanted to do something different for the apparition of Cinderella’s mother, and find an evocative way to present her,” Schmidt says. The end result is the mother’s face in one of the trees in the forest. The projection of the giant’s shadow was rather complicated, as there is a mix of live action with the projection, and the sound track had to be cued with very close timing. “It took a lot of work in Los Angeles to get it right, but the subtlety of the gestures make it look as it the giant is listening.”

Seeing all the elements come together confirmed for Schmidt that the entire creative team was on the same page. “The musical itself is so touching and funny, and beautifully written, you want it to have one sensibility. I think we achieved that.”

Fairy Lights

“Winning the Tony was a thrill,” says Brian MacDevitt, who was honored for his lighting design for Into the Woods. “The lighting follows the investigating that set designer Douglas Schmidt did to give the musical a literary point of view, with ornate, illustrated children’s books spinning and popping open.” As if you entered the fairy tales through the text,” MacDevitt notes. Clickstrip runs along the edge of the book layers to give them a pop-up effect.”

set model of Red Riding Hood's granny's cottage.

Following the lead set by Schmidt’s sets, the lighting adds an extra vibrancy to the natural colors witnessed in nature. The show follows a big arc, from the dappled sunlight of a beautiful forest to a devastated, almost war-torn look,” MacDevitt explains. “The scenery is painted with fairly neutral colors so the lighting could push deep greens, blues, and ambers. The lighting is more colorful, with a very saturated palette. It needed to be magical.”

In the numerous scenes that take place in the forest, MacDevitt layered the light, with overlapping five to six different colors and various templates, including leaves. “I tried to really mix things so they weren’t recognizable to look at,” he notes. The layers range from large breakup templates to GAM’s pointilism patterns, with the size of the patterns varying with the intensity of the colors. “A source, such as the moon, would be portrayed by the densest templates, where the least light gets through, and the palest colors, and layers of larger breakups and deeper colors would follow.

MacDevitt describes his rig, as supplied by Fourth Phase, as “fairly conservative,” and that of a traditional Broadway musical. “There is no special truss, just booms and overhead pipes,” he adds. The rig does include 40 automated luminaires; a mixture of 21 ETC Source Fours on City Theatrical AutoYokes, and both 17 Studio Beams® and 12 X Spots from High End Systems. The show is run via one Wholehog II and one ETC Obsession III console.

MacDevitt worked with programmer David Arch, associate LD Jason Lyons, and assistant LD Yael Lubetzky. In working with projection designer Elaine McCarthy, MacDevitt strove to incorporate the projections seamlessly, actually using the video projectors as sources.

“There is subtle movement in the moving lights. Every choice we made was influenced by the score, so there are not too many moments of flash, except for the vogue-ing by Vanessa Williams in her transformation scene,” MacDevitt says. Other moves in the automated fixtures helped during scene shifts, adding to the movement of the scenery. “You never see a template change or the gobos flipping, yet there are a few visible changes of focus, zoom, and color.”

–ELG

Fee Fi Fo Fum

You notice sound designer Dan Moses Schreier’s work on Into the Woods before you even sit down in your seat—the preshow features a collage of bird cues emanating from various parts of the theatre, all chirping and tweeting happily away. These fine feathered friends can be heard during transitions throughout the first act, a far cry from the ominous sounds of the scavenger birds Schreier unleashes for the much darker second act. Such inventive specificity is par for the course for Schreier, a designer best known for his work on straight plays whose extensive collaborations with director James Lapine (Dirty Blonde, The Diary of Anne Frank, Twelve Dreams, Golden Child, A New Brain) led to working on this revival.

While the bird cues were relatively simple to pull off, Schreier and his crew (associate Simon Matthews and assistant Fitz Patton) had much bigger fish to fry. The giant casts a, um, giant shadow over the proceedings in Act II of Into the Woods—the grieving wife of the giant slain in Act I who has come down to earth looking for revenge is heard but never seen aside from shadowed video projections by Elaine McCarthy—and it was up to the sound designer to create a believable, threatening, but not overpowering presence.

“The biggest challenge was creating the giant,” Schreier explains. “It takes up a large part of Act II. And because it evolved as we were working on the piece, it took us a long time to get to where it got finally. Not only were there technical issues involved, which were considerable—the synching with the video became a big issue—but also because of what we wanted the sounds to be.”

The genesis of the giant began in rehearsals, courtesy of musical director Paul Gemignani. “He had a giant bass drum in the rehearsal room in order to begin to give the actors a sense of what the approaching giant might do to them emotionally,” Schreier says. “That became my marker for how to build the giant, just jotting down when Paul hit the drum, and taking note of when the steps should begin to be heard, and when they have to arrive and disappear.” From there, it became a matter of adding different layers of sounds that would go with the moving giant—the brushing of leaves and trees, the cracking of branches, not to mention the big thud when the male giant hits the ground in Act I.

“I also decided,” Schreier adds, that as the giant moves, the animals in the forest are being displaced, so whenever the giant approaches, you’re hearing birds fluttering and going off in different directions in order to give a real sense of being within the forest. It’s not just the giant steps, there’s a whole environment that moves very much in the space as the giant approaches.”

The next step was the addition of McCarthy’s video. As her ideas were added to the mix, more sound would be added, video would be moved around, or some of the scenery would be shifted to create the total picture. During this time, the female giant’s vocals were added to the mix; originally done by cast member Linda Mugleston as a marker, the final voiceover, by Dame Judi Dench, was added while the production was still in tryouts in LA. Dench was in a recording studio in London, Lapine and Schreier were in a studio in LA, and Schreier recorded her performance via a digital link while Lapine provided direction over the phone.

Schreier generally prefers to record as many effects himself as possible, then opts for the standard libraries, using a sampler to make them all sound as different from the original sources as possible. He also goes for extreme layers, rarely opting for a single effect, except obviously in the case of the cow, though even that was altered. He used the Performer music-sequencing program for much of the show, which was especially useful with the giant cues. “Performer was invaluable in making that happen,” he says. “Version 3.0 is new and it has these things called MOTU Panners. It’s very flexible in creating how you want sound to move within a space and how many speakers you want. It has a great capacity for linking things together, and you can also track through reverb.”

Speakers include the d&b E3 full range compact speaker, an increasingly popular choice among theatre sound designers in the US (it’s been a fixture in the UK for a couple of years now), as well as EAW JF-80 and JF-60s and Meyer’s new MM-4 compact speaker. Schreier also used a variety of subwoofers, including Meyer UPA-1Ps, EAW SB-48s, and Sunfire True subwoofers, which were placed all over the theatre, one, to deal with the giant effects, and two, to help with the orchestra. Control comes via the Cadac K-Type, the small, sidecar console, which supplier Masque Sound custom-modified to Schreier’s specifications, and which, needless to say, provides a smaller footprint than standard-sized boards. Microphones included AKG CK91s, DPA 4022s, Sennheiser MKH-80s, and Shure SM-58s. There are also a handful of the new Sennheiser SK5012 mini UHF lavalier transmitters on the show.

Some eyebrows might have raised at the prospect of Schreier, best known for his effects-driven work on straight plays (Topdog/Underdog, The Diary of Anne Frank, The Tempest), working on a big Broadway musical. His long collaboration with Lapine helped, but, as the designer notes, he’s also a composer. “When I got hired the refrain that kept coming was ‘Remember Dan, this is a chamber piece, it’s not a full-blown rock piece, it shouldn’t be amplified in a very strong way. And I kept telling everyone, ‘I’m your man.’ Because I’m a music lover. I’ve never been averse to musicals; that’s not where my reputation is, but I’m very happy to do it.”

–DJ